30 November 2022

While it is still too early to conclusively remark that we are in a new era of deglobalisation, nevertheless it is likely that we are now seeing some significant shifts in globalisation, which is being redefined by geopolitics, and increasingly nationalism and protectionist measures. The implications for investors are likely to be long lasting.

Globalistion – reversal or slowdown?

The recent rise of economic nationalism, driven in no small part by an increasingly populist political agenda in many countries and regions across the globe, has combined with disruptions arising from the COVID-19 pandemic to herald predictions that we have reached the end of a prolonged period of globalisation, which has been the predominant global economic theme for much of the period since 1945.

Indeed, some commentators are asserting that we have now entered a period of deglobalisation. This has been defined by research institute Chatham House as “a movement towards a less connected word, characterised by powerful nation states, local solutions, and border controls rather than global institutions, treaties, and free movement.”

Looking at the historical context and particularly more recent trends such as the deceleration in world exports as a share of global GDP since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), examined in our previous article, it is certainly apparent that a slowdown of globalisation is underway. However, we believe these changes are not indicative of deglobalisation, but more accurately reflect a slowing of globalisation, which we can characterise as ‘slowbalisation’. Our contention is that globalisation is changing shape, partially in response to the prevailing populist political narrative, but also driven by technological developments, some of which have accelerated in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We examine these factors, and their investment implications, in detail below.

Contrasts and shifts in globalisation

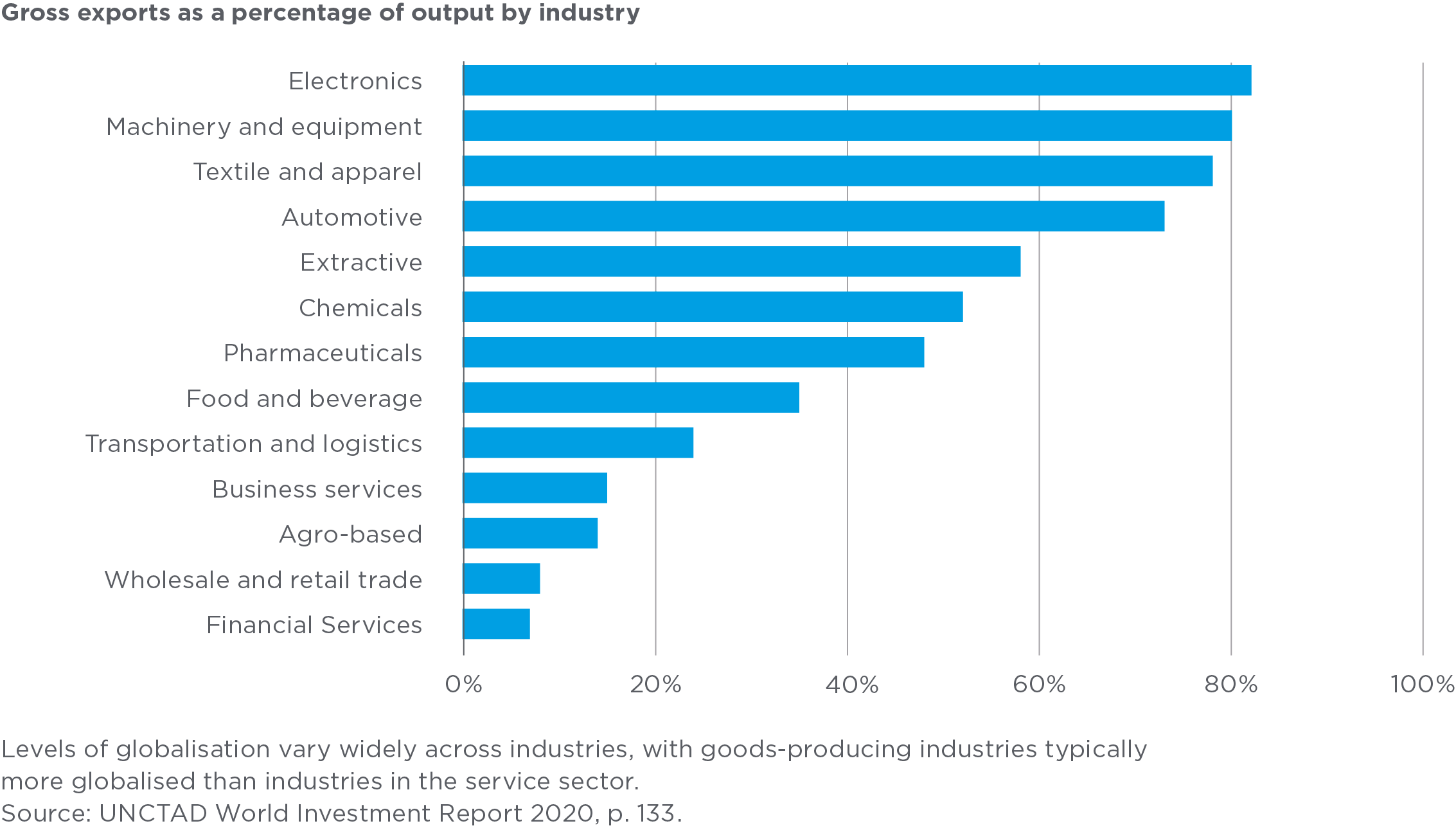

The first point to note is that globalisation has not been uniform across sectors. The chart below highlights that manufacturing industries are typically more globalised than the services sectors. The simple reason why industries such as electronics, machinery, textiles and automotives are more globalised is that it far easier to ship their components and goods around the world. In contrast, sectors such as financial services, agriculture, business services and wholesale and retail trade are by their very nature more domestically orientated.

For those industries that are global, there has been much talk of a shift towards reshoring production, with politicians keen to highlight the potential for boosting employment prospects, while stressing the virtues of avoiding trade with unsavory regimes. However, whether this will herald a substantive shift towards reshoring depends on several factors.

Most significantly, compared with China and other emerging economies, factories and sectors in the West must navigate a tougher environmental and regulatory framework, even before considering associated labour costs and the industrial ecosystem. Crucially, the establishment of any manufacturing base in Western economies is more expensive from an operational perspective, not just in terms of wages but also minimum standards on emissions, building regulations and materials, and health & safety.

Despite the prevailing rhetoric, it is more realistic to expect that any reshoring will be very selective and most likely provide more of a boost to automation; robotics rather than human resources. Any such capital expenditure will require a strong emphasis on higher productivity, through modern plants with less wastage and greater energy efficiency, to be justifiable from a return on investment (ROI) perspective.

With electronics highlighted above as one of the most globalised sectors, the semiconductor industry represents an interesting case study in examining the potential for reshoring. Over the past three decades, the industry has evolved rapidly and has been both a significant beneficiary from, and driver of, globalisation. US and European companies have switched to fabless business models, creating all the designs for their chips domestically but outsourcing the physical manufacturing to a foundry partner based in Asia.

![]()

The chart above highlights that US and European share of semiconductor manufacturing capacity has fallen substantially, with the US accounting for just 12% of global capacity by 2020. The globalisation of the supply chain can be also illustrated by considering a specific product – the Apple iPhone. Designed in California, with memory and display supplied from Korea and Japan, hardware components manufactured in Taiwan, and then with the final product assembled in China and subsequently shipped to customers worldwide.

Semiconductors have become increasingly vital for a functioning global economy, with components for mobile phones, PCs, cars and factories transported worldwide but with production heavily focused on Asia. This makes the sector particularly sensitive to any sustained escalation in geopolitical tensions, and has led to calls for a reshoring of production to reduce reliance on Asian manufacturers.

Accordingly, capacity is beginning to spread out geographically, with Intel establishing leading edge fabless production in Ohio and Germany, Samsung building manufacturing facilities in Texas while in 2020 Taiwanese foundry producer TSMC announced the construction of a chip-fabrication plant in Arizona. However, the cost of establishing such a manufacturing capability in the US and other Western economies, replicating an Asian production base, is huge. TSMC’s plant in Arizona alone cost $12bn, while Intel is expecting to spend $80bn in Europe. Moreover, it is far from straightforward to build an integrated semiconductor capability, encompassing intellectual property and specialist equipment on the required scale, particularly at the leading end of the market in sub-sectors such as top-end chips for AI. Given these constraints, it is hard to foresee a wholesale reshoring of semiconductor manufacturing capacity.

One of the major themes in recent analyses of globalisation is the contention that the global economy could be fracturing along regional lines. We would argue that it is easy to conflate deglobalisation with longer-term trends, such as a reduced dependency on any single country, most notably China, and increasing diversification across the supply chain. This shift in supply chains has become very apparent in the footwear and apparel industry. US and European footwear imports were dominated by China in 2014, but now China’s share of the supply chain has shrunk significantly and shifted to other countries, as increasing efficiency and expanding capacity are drawing apparel manufacturing to rising hubs, including Vietnam, India, Bangladesh and Mexico.

Source: Nike, Adidas, US Department of Commerce Office of Textiles and Apparel (OTEXA), Morgan Stanley, May 2022

For leading US and European producers Nike and Adidas, the chart above highlights that Vietnam is now the biggest manufacturer of footwear supplies.

Both Vietnam and Bangladesh offer the benefits of low cost production, while from a logistical perspective Mexico offers the advantage of near shoring for US companies. Political factors have also played a part, as China produces one-sixth of the world’s cotton and 80% of that is from Xinjiang region, which is associated with slave labour and the suppression of Uyghurs. As a result, Western companies and governments are keen to avoid exposure, with the US recently introducing regulations requiring companies to prove that imports from the region have not been produced using forced labour.

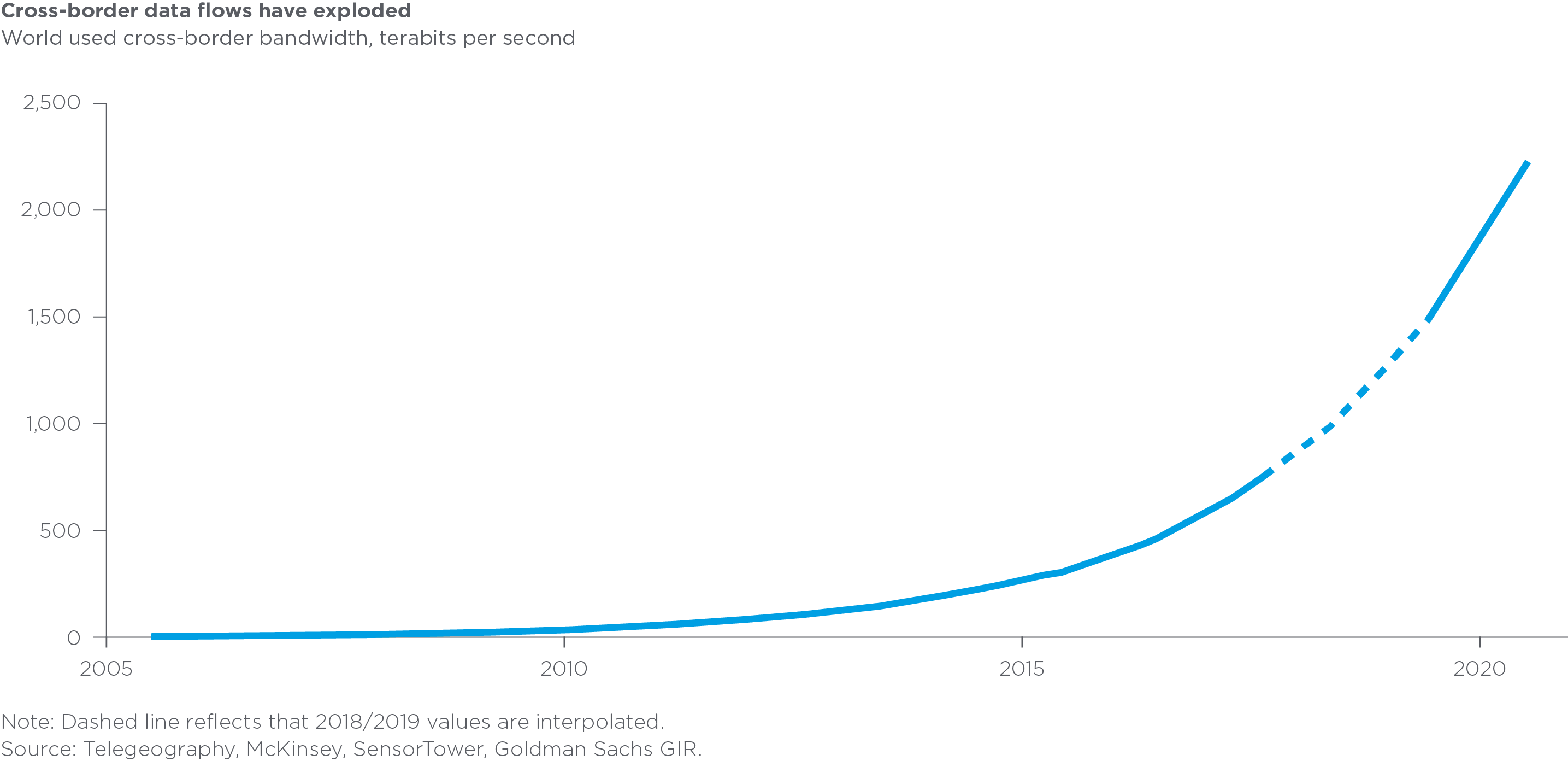

Aside from global trade and manufacturing, digital connectedness remains a powerful trend. Remote working has now become the accepted norm for white collar jobs, facilitating a more geographically dispersed workforce. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that many people can work from anywhere, using a combination of video, email and file sharing, while outside of the work environment social media and gaming are not limited by geography. The impact on cross-border data flows has been dramatic, as the pandemic has accelerated these trends with the growth of internet traffic, dominated by the global technology giants.

Source: Bank of America, May 2022

The implications for investment portfolios

As geopolitics becomes more polarised, investors need to be increasingly aware of where the fault lines reside, and where possible, incorporate the risks of protectionist measures into their investment decisions. A good recent example is the China/US spat on foreign listing and the US SEC's (Securities and Exchange Commission) threat to de-list around 200 Chinese securities from the NYSE as the regulator is "unable to verify their financial audits." We would also observe that the diversification of company supply chains away from China highlighted above, in favour of a more regional hubs, is benefitting certain South East Asian nations, notably Vietnam, Bangladesh and Indonesia.

Perhaps one of the most pronounced effects of globalisation has been deflation, particularly in the price of durable goods. The biggest impact of any reversal or slowdown in globalisation could therefore be persistently higher inflation, or at least more volatility in inflationary expectations. Even if inflation moderates from here, residual inflationary pressures are likely to remain higher. Furthermore, we might also expect to see a fall in real incomes, lower average living standards and a decline in consumer demand as interest rates rise and asset prices fall.

The rising tide of economic nationalism is likely to re-define corporate behaviour, at least to some degree. As we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic, nation states prioritise vaccine production for their own populations ahead of others, in effect limiting corporate behaviour to profit maximise. In addition, with regards to issues that impact on national security, we have seen both the US and Europe pivot towards the prioritisation of reshoring semiconductor production, notable examples being the recent US CHIPS for America Act and the FABS (Facilitating American-Built Semiconductors) Act.

Most likely, investors would have begun 2022 putting a low probability on Russia invading Ukraine. This conflict is likely to be drawn out, with Putin deliberately weaponising both energy and food production to impact Western economies. By the end of this year, this could result in energy rationing in both Germany and Japan, although a potential silver lining is that we are likely to see a concerted effort to move away from European dependence on Russian oil and gas with increased investment in renewables.

Escalating geopolitical tensions, not just the Ukraine conflict but also between the US and China, and China and Taiwan, are likely to result in companies reassessing their supply chains, particularly in sectors that have depended on just-in-time inventory and lean forms of manufacturing. This is most likely to have major implications for working capital and productivity within certain sectors, particularly the autos industry. However, companies with complex supply chains will face an uphill challenge to reshore or near shore production, given the prohibitively high costs involved.

Combined, these factors are likely to put considerable pressure on company profit margins and earnings growth in the foreseeable future, placing greater onus on investors to identify those companies who can thrive in this 'new' normal.

Lastly, currency markets are likely to become considerably more volatile. Countries with large debt burdens appear to be the most vulnerable in these conditions, particularly where this is combined with an energy price shock. Energy importers such as mainland Europe, the UK and Japan have already suffered a negative impact on their currencies, whereas energy-neutral countries such as the US have fared better.

Conclusions for multi-asset funds

Considering these implications for a traditional 60/40 portfolio, where 60% is invested in equities and 40% in bonds, investors will need to rethink how they can be prepared for market conditions where lower risk-adjusted returns are likely.

Firstly, stagflation could become a more dominant theme as globalisation changes shape. This is likely to take the form of higher and more volatile inflation, accompanied by a rising cost of financing for both companies and governments, weakening economic growth and a continuing decline in real wages. Any conventional multi-asset portfolio is likely to be challenged under such a scenario, not just equity markets but also bonds, as the combination of higher inflation and rising interest rates is likely to put further pressure on bond markets.

Investors and their asset managers may well have to re-think asset return assumptions and come up with new approaches to portfolio construction. We believe alternative assets are likely to play an increasingly important role in institutional portfolios, particularly where such assets can provide diversification against equity market risk and inflation-linked cash flows, reducing volatility and enhancing risk-adjusted returns. Also, the transition from fossil fuels to greener forms of energy should provide opportunities in alternative assets that are well placed to benefit from increased investment in renewable energy sources.

Within equity markets, investors may need to be more flexible, as economic cycles could compress, as well as being more selective, recognising that not all business models might thrive in this new environment. Companies with strong competitive positions, selling products and services that are sought after by consumers or are critical to the functioning of other firms’ activities will likely be best placed, both to pass through higher pricing to protect profit margins, but to also benefit from stickier customer bases.

In addition, businesses with strong balance sheets should be relatively well placed to weather these more challenging conditions. The lesson from the lost decades of Japan is that companies may have to become more self-sufficient and less dependent on debt markets to avoid costly refinancing activities. The era of cheap and plentiful debt is most likely over.